Officers face possible misconduct allegations

Demands were growing last night for a criminal inquiry into alleged misconduct by senior police officers after a report laid bare the scale of the failures in Scotland Yard’s investigation into a non-existent Westminster paedophile ring.

Sir Richard Henriques’s long-awaited review concluded that officers had unlawfully misled a judge to obtain warrants to search the homes of public figures falsely accused of child murder, rape and torture.

The report revealed that it was the former deputy assistant commissioner Steve Rodhouse who had committed the Met to saying publicly that it believed the claims of the fantasist Carl Beech, the alleged victim, without reading his inconsistent accounts of abuse by politicians, spy chiefs and military officers. The review described this as a “serious failure”.

That revelation will raise questions for Dame Cressida Dick, the Met commissioner, who had claimed that the force’s description of Beech, known at the time only as “Nick”, as “credible and true” had been simply “a mistake” made on the spot by an officer who was being “pressed” by the media.

More than three months after Beech’s conviction for fabricating his allegations, the Met succumbed to calls from those he had falsely accused to release large sections of the Henriques report yesterday.

The Times understands that Sir Richard, a retired High Court judge, has privately lobbied for publication of his report, which was initially published in heavily redacted form in 2016, and is concerned that no officers have been held to account for the failings he identified.

A cabinet minister told The Times that the police failings, especially over the search warrants, “should not be left to lie”. They added: “Knowingly misleading the courts is extremely serious and of huge gravity. There needs to be a full and frank investigation into this, which could lead to a criminal inquiry into whether the course of justice has been perverted by the police.”

Sir Richard’s report said that:

•Several opportunities to drop the case were missed because officers were reluctant to question the credibility of their star witness.

•Met detectives never examined Beech’s phones or computers, which would have revealed not only how he had fabricated his story but also that he was downloading child abuse images.

•Tom Watson, the Labour deputy leader who met Beech and urged him to go to police, “created further pressure” on officers and sent hundreds of pieces of information to police.

•A BBC reporter showed photographs of a missing child to Beech, who later said he had witnessed the boy’s murder.

•The Met failed to tell the Tory former home secretary Lord Brittan of Spennithorne during his lifetime that he had been cleared, even though officers and prosecutors had concluded that there was no evidence against him.

The police complaints watchdog will explain next week why it has already exonerated five officers of misconduct. Four of those, including Mr Rodhouse, were cleared without being interviewed. He has since been promoted to a senior role at the National Crime Agency, for which he is paid £240,000 a year.

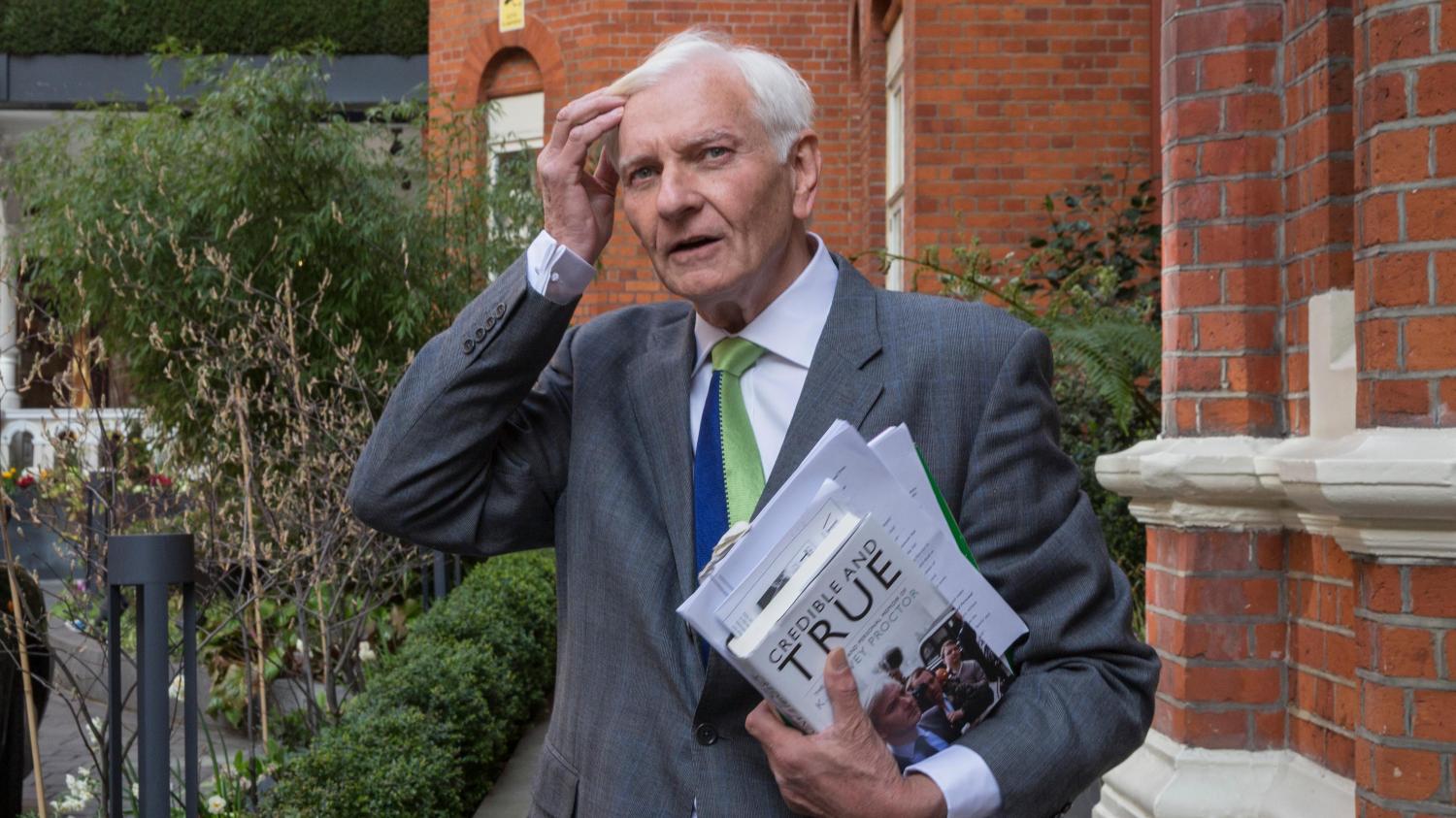

Operation Midland ran for 18 months from 2014-16. Police searched the homes of Lord Bramall, 95, former head of the armed forces; Harvey Proctor, 72, a former Tory MP; and Lord Brittan, who later died aged 75. All three were interviewed under caution.

The bungled investigation, a subsequent criminal inquiry into Beech and legal costs related to compensation claims have run up a bill to the taxpayer of more than £5 million.

Mr Proctor said that a further review ordered by Priti Patel, the home secretary, was only a “first step” and demanded that “an outside force be called in to investigate these allegations”.

He said that Northumbria police, which secured Beech’s convictions for perverting the course of justice, fraud, voyeurism and paedophile offences, was ideally placed to take on the case. Beech was given an 18-year prison sentence in July.

Mr Proctor’s lawyer, Geoffrey Robertson, QC, said the Met had acted “incompetently, negligently and almost with institutional stupidity”. The human rights lawyer said that reforms were needed, including greater transparency around search warrant applications. Mr Robertson said: “The negligence in this case was so gross and so repetitive and so damaging to innocent individuals that the home secretary should decide that the time has come for the UK to permit victims of police incompetence to sue for negligence”.

Mr Watson said that the Henriques report contained “multiple inaccuracies regarding myself”. He denied he had had undue influence over police inquiries.

Sir Stephen House, the Met deputy commissioner, said the force was “deeply, deeply sorry for the mistakes that were made” but insisted there should be no further misconduct inquiries into individual officers. Mr Rodhouse said he was “sincerely sorry for the distress to innocent people and their families”.

Four years on, I hope for justice

More than four years after I was accused of unspeakable evils by a liar whose fictions were amplified with the full force of the biggest police service in the land, I am a changed man (Harvey Proctor writes). This is what the Met police have done to me. I wish it was different.

In an effort to stay sane, I focus on the facts — the dates, the lies and the inconsistencies. I do not let their weasel words of apology distract me. This week the home secretary announced that HM Inspectorate of Constabulary would conduct a review to ensure that lessons had been learnt at Scotland Yard. While I welcome this as a first step, the Home Office must go further.

At the moment a retired High Court judge has said in great detail and argued very cogently that the force obtained search warrants illegally. I continue to call for an outside police force to be called in to investigate. To my mind this should be Northumbria, which exposed the lies the Met failed to spot.

The Independent Office for Police Conduct is not fit for purpose, and has worked hand-in-glove with the Met to cover up the failings Sir Richard has laid out.

The failings here are symptomatic of a deeper sickness that must also be addressed. The errors made were the result of a culture of incompetence and negligence at the heart of the Met’s management and ethics. To remedy this I believe that a public inquiry should follow.

This matter does not end here for me. I lost my house, my job and years of my life while officers responsible were enriched, ennobled and allowed to retire on public pensions. I am suing the Met police because of the damage they have done to me by reversing the centuries-long principle that one is innocent until proven guilty. I sincerely hope that justice is now done.