Carl Beech is a liar, fraudster and paedophile.

But for 18 months between 2014 and 2016, he was the star witness in a high-profile investigation into allegations of sexual abuse and murder, involving MPs, generals and senior figures in the intelligence services.

Those falsely accused had their properties raided, and one of them – ex-MP Harvey Proctor – lost both his home and his job.

At the time, Beech, a former NHS paediatric nurse, was working as a hospital inspector with the Care Quality Commission. He was also the governor of two schools in Gloucestershire where he lived.

Police referred to him only using the pseudonym “Nick”, to protect his identity.

His claims that he and others had been the victim of sexual abuse by a “VIP ring” in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and that he had witnessed three child murders by members of the same group, featured prominently on BBC News, in a British national newspaper and on a now-defunct website called Exaro.

However, while he was promoting his lies, Beech was busy downloading child abuse imagery and covertly filming a teenage boy.

The investigation – known as Operation Midland – would cost some £2.5m. But by the time it was wound up, not one arrest had been made.

Beech, however, received more than £20,000 in public money as compensation for injuries he claimed were inflicted during the alleged abuse – injuries he had never actually suffered.

After a 12-week trial, Beech was sentenced to 18 years in prison, having been found guilty of 12 counts of perverting the course of justice, one of fraud, and several child sexual offences.

But what led the 51-year-old divorced father of a teenage son to make the allegations in the first place?

Abuse ‘parties’

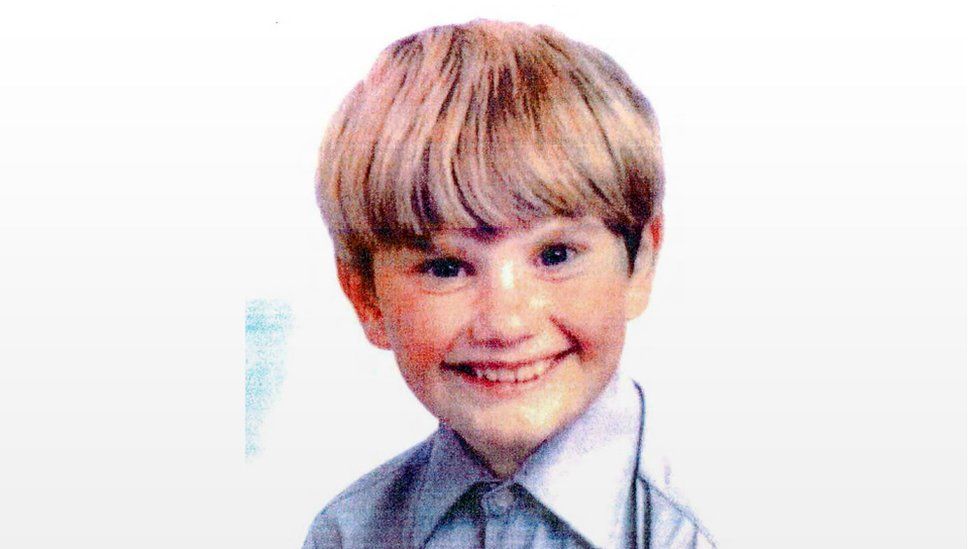

Born as Carl Stephen Gass in Wrexham in 1968, his parents separated when he was young.

In 1976, his mother Charmian remarried Major Raymond Beech, a soldier based in Wiltshire.

Carl took his stepfather’s surname and spent time in the county living in a military property. But when that marriage broke down he moved with his mother first to Bicester in Oxfordshire, and then, in 1979, to the London suburb of Kingston upon Thames.

It was this period of his life that Beech would build his allegations around, claiming that between the ages of seven and 16 he was abused by a powerful paedophile ring that included the late British media personality Jimmy Savile.

In 2012, Beech approached the Metropolitan Police, which had launched Operation Yewtree to investigate alleged sexual abuse in the wake of the Savile scandal.

They referred him to Wiltshire Police as the most relevant to his claims.

Speaking to a detective from Wiltshire, Beech claimed he had been abused by his stepfather, before being introduced by him to a group of other alleged abusers including Savile, an unnamed lieutenant colonel – whom he identified as the ringleader – and up to 20 other unidentified men.

The only two people he named were Raymond Beech and Savile. When asked by the police for other names, Beech said that he didn’t know them.

He claimed that he was regularly taken out of school to be abused and that this continued even after his mother had separated from his stepfather.

He said that over the nine years, an unnamed driver took him to abuse “parties” at military bases, and later at central London locations.

He also told detectives that a friend called Aubrey had also been abused by the same group.

But after examining the wider claims, Wiltshire Police decided not to take any further action.

The inquiry had found that Charmian had only been married to Raymond Beech for a few months, and that she had subsequently sought a non-molestation injunction against him.

Army records suggested he had a drink problem, had been violent towards Charmian, and retired from the army on mental health grounds after they divorced. He died in 1995.

‘Carl Survivor’

In 2013, Beech came across a post on an abuse charity website. Documentary makers were looking to interview male survivors of Savile for a programme to be broadcast on a satellite TV channel.

Beech readily volunteered, and appeared anonymously using his middle name Stephen.

The documentary didn’t make much of an impact, and Beech continued building up his sexual abuse allegations online. It was this activity that gained him far greater attention.

In the years immediately following the Savile scandal, parts of the internet were rife with allegations of historical sexual abuse by prominent people.

And Sunday newspapers regularly ran stories about VIP abuse rings and alleged cover-ups.

At the time, some MPs – including the now Deputy Labour Leader Tom Watson – were prominently campaigning on the issue of historical abuse.

Several well-known people had been arrested – and some charged and convicted – for non-recent sexual offences.

But the rumours online went beyond these inquiries and raised the spectre of a far bigger conspiracy.

Beech’s online allegations, therefore, came amid claims of establishment cover-ups, controversies over lost dossiers of evidence, calls for a national inquiry into child abuse, and rumours about which famous figure would next be revealed as a paedophile.

His own accounts, which would eventually draw together several existing conspiracy theories, presented himself as the victim of a sadistic culture at the heart of British power.

Into his story went several men and locations already the subject of online rumours, others who were known to be under investigation by separate inquiries, as well as senior figures within the armed forces and military intelligence.

In total, he was accusing 10 new men.

Beech eventually went on to tweet and blog under the name “Carl Survivor”, with graphic posts about sexual abuse and torture appearing on a website for those allegedly abused as children.

In one post he referred to “very powerful people” who had controlled every part of his life.

In others, he penned poems describing nightmarish events like being locked in a room full of wasps.

“Sometimes when I had broken the rules, been bad. They shut me in a room of wasps all mad,” he wrote.

A retired child protection manager – Peter McKelvie – brought the posts to the attention of a BBC journalist, who met Beech but didn’t look into his claims or follow up with a story.

Articles about Beech’s claims and a subsequent police investigation did, however, begin to appear on the Exaro News website. Mark Conrad, a then Exaro reporter, met Beech and maintained regular contact with him.

As he went through Beech’s allegations, Conrad showed him 42 images, apparently as a form of picture test, with Beech picking out people he had already named.

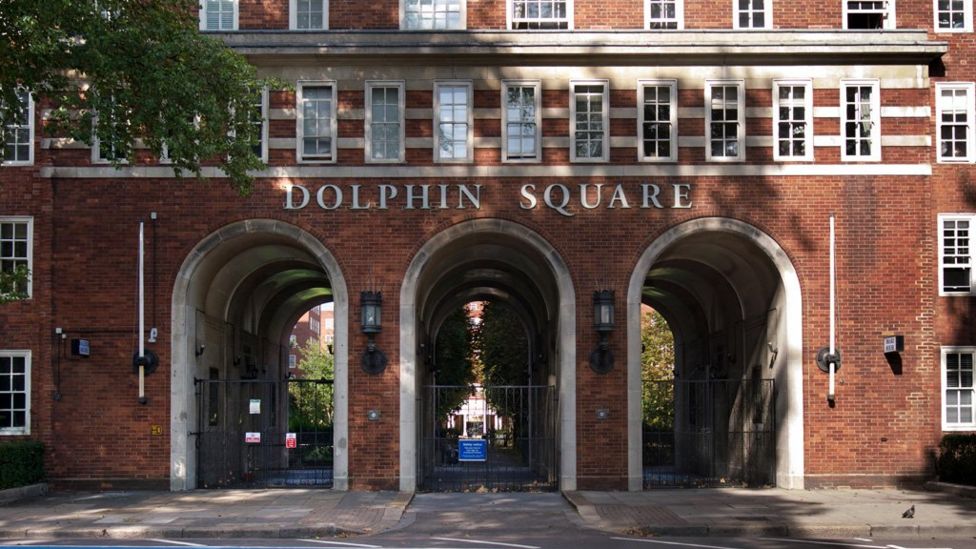

The pair also visited locations apparently relevant to the allegations, including Dolphin Square, an apartment block in central London, which has long been home to MPs and other notable figures, and the London home of the former Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath.

‘Nick’

Beech was also taken to Parliament to meet Tom Watson, who subsequently stayed in touch with him.

During his later interviews with detectives from the Met, Beech said Watson had been part of a “little group that was supporting me and trying to put some of my information out there to try and encourage others to come forward”.

The MP had previously triggered various Met inquiries after passing the force a series of allegations.

Beech had been given the pseudonym “Nick” in Exaro’s coverage of his allegations. These came to the notice of Scotland Yard, who asked for access to their source.

Beech met detectives, and went on to give them 20 hours of recorded testimony. But in contrast to his earlier interviews with Wiltshire Police, Beech now started giving detectives multiple names – falsely implicating a string of famous figures at the heart of British public life in the 1970s and 1980s.

From the military, he named two former heads of the armed forces, Lord Bramall and Sir Roland Gibbs, and another senior general, Sir Hugh Beach.

The former chiefs of MI5 and MI6, Sir Michael Hanley and Sir Maurice Oldfield, as well as the former Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath, former Home Secretary Lord Brittan, and the ex-MPs Harvey Proctor and Lord Janner, also became part of his story.

Beech alleged his stepfather handed him over to this “group” and that it operated using chauffeurs who collected him from school or his local railway station.

Despite his apparent strong recall of incidents involving famous names, he offered nothing tangible about the various drivers, witnesses and non-famous abusers his account incorporated.

Murder claims

Sadistic abuse was alleged to have taken place at various military sites in southern England, before the locations switched to central London hotels and properties, after he moved to Kingston with his mother.

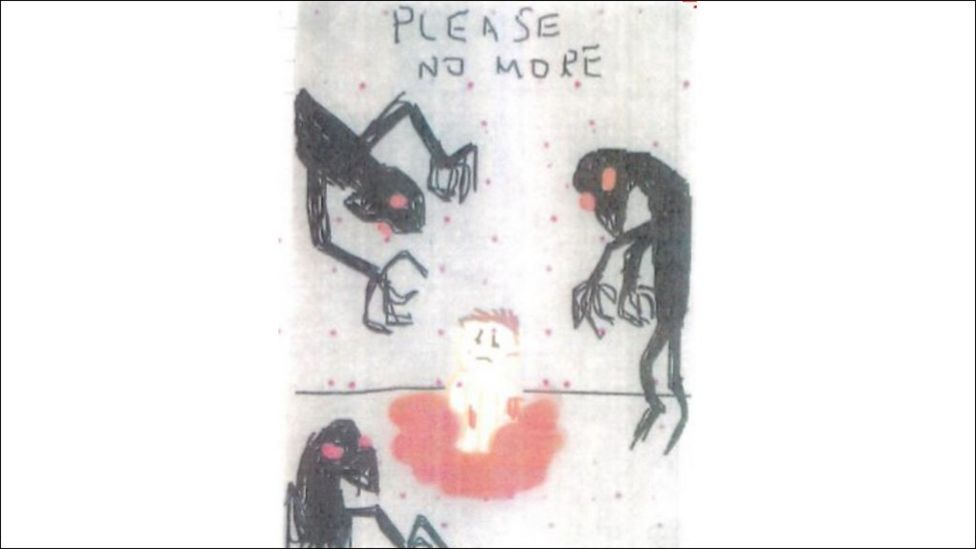

He claimed other boys were present at the sessions, which were said to include torture and elaborate punishments such as electrocution, being used as a human dartboard, and having spiders tipped over his naked body.

“I couldn’t scream because if you screamed then the chances are one would go in your mouth,” he told detectives.

Beech even said the MI5 boss oversaw the abduction of his dog and “collared” him outside school to threaten that if he failed to follow orders the pet would come to harm.

He provided the first names of other boys, including Aubrey and someone he claimed to still be in touch with, who was given the pseudonym “Fred”.

Most significantly of all, Beech alleged he had witnessed the murders of three children. These were claims that he had not previously made to Wiltshire police.

One – a schoolmate called Scott – was said to have been deliberately run over by a car in a Kingston street as some kind of warning by the group.

The second – an unnamed boy – was alleged to have been stabbed and strangled by Harvey Proctor in a London townhouse.

The third, also unnamed, was said to have been beaten to death by Proctor and Sir Michael Hanley, while Lord Brittan and several children watched.

Beech claimed that, on a separate occasion, Proctor was only prevented from removing his genitals with a penknife after Sir Edward Heath intervened.

Scotland Yard launched a disastrous murder investigation, codenamed Operation Midland.

Within weeks – before any major investigative steps had been taken – there was a high-profile appeal for witnesses.

The accuser was publicly praised by the officer overseeing the inquiry, Det Supt Kenny MacDonald, who said detectives considered his account to be “credible and true” and stated: “We do believe what Nick is saying”.

Details of Beech’s murder allegations had already appeared on the Exaro site and in the Sunday People newspaper. In November 2014, a television interview with him had led the main BBC News bulletins.

The men he accused were not named, but it was reported that they included senior figures from politics, the military and law enforcement.

His contact with the media fed into the police investigation.

Damning report

A later review of Operation Midland by retired judge Sir Richard Henriques said journalists making their own inquiries had provided an “unwelcome intrusion” by showing him pictures of suspects, potentially relevant locations, and missing or murdered boys.

BBC home affairs correspondent Tom Symonds, who interviewed Beech, had shown him images from recent newspaper stories of two boys who vanished from London in the late 70s and early 80s, one of whom Beech subsequently claimed was the victim of the second murder he claimed to have witnessed.

The child – Martin Allen, a 15-year-old who disappeared in 1979 – became a focus of the police inquiry and detectives contacted his family.

Beech claimed Allen had been held at an address in Pimlico, central London, before being killed. But he only identified the property after he had been shown an image of it by Exaro’s Conrad.

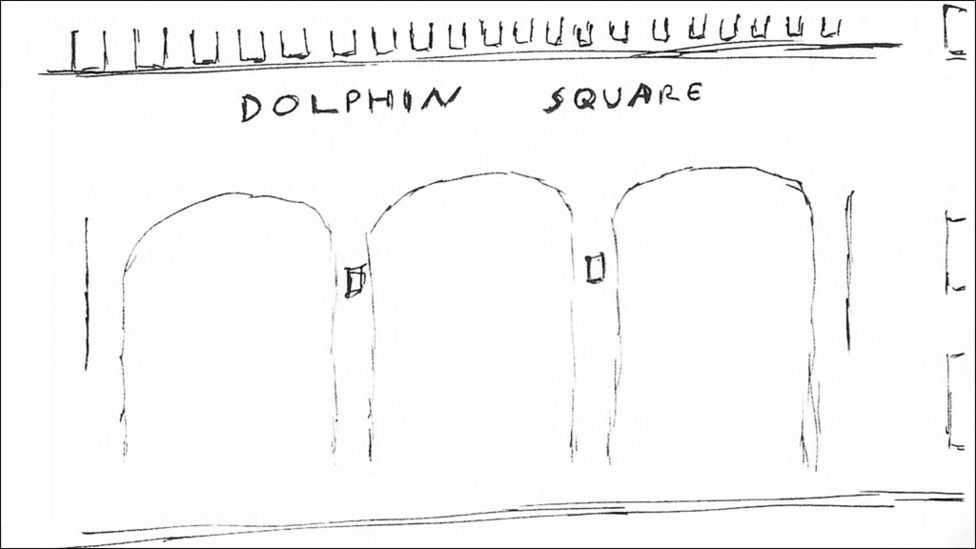

Beech then drew a picture of the property in a notebook, but claimed to police that he had done it sometime before from memory. The flat had once been occupied by a paedophile called Alfred Leslie Goddard, who was connected to a murderous gang of abusers that included Sidney Cooke – a child killer and one of Britain’s most notorious paedophiles.

Other location sketches were also given to police and Beech later falsely claimed that he recognised several places from memory – such as military bases and the former homes of suspects – when taken on site visits by detectives.

The reality, though, was that he had carried out extensive research about people and places on the internet.

It was enough to convince Scotland Yard.

When Lord Brittan died in January 2015, Tom Watson wrote an article in the Sunday People newspaper to accompany its revelation that the peer was under investigation by Operation Midland.

Watson wrote how one “survivor” told him that Lord Brittan was “as close to evil as a human being could get in my view”.

That person, it can now be revealed, was Carl Beech.

In the article, Watson wrote: “It is not for me to judge whether the claims made against Brittan are true.”

But, the following month, he tweeted: “I think I have made my position on Leon Brittan perfectly clear. I believe the people who say he raped them.”

In March 2015, Operation Midland raided the homes of Harvey Proctor, Lord Bramall, and the recently deceased Lord Brittan.

Proctor, who lived and worked at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire, which was owned by the Duke and Duchess of Rutland, subsequently lost both his job and home.

Beech was informed of the raids in a phone call from a detective who was standing in Harvey Proctor’s house.

The raids were reported in the media, with a consequent loss of anonymity for the accused.

Just before news about the raids on Lord Brittan and Lord Bramall was reported by Exaro, Beech emailed his main police contact DC Danny Chatfield to say that the website wanted to publish a piece encouraging other victims to come forward and wanted a quote.

Beech sent a draft set of comments, which included the line: “There are some excellent detectives from the Metropolitan Police who are working on the information that I have given to them.”

The detective replied: “The wording is fine with us, so please go ahead.”

He then sent Beech the approximate locations of the searches, saying Exaro had been asking for them.

Beech wrote back: “Thanks for telling me the other places.”

However, the search warrants were flawed and contained inaccurate information.

Compensation payment

It was one of many errors.

The officers who interviewed Beech had not read his earlier Wiltshire interview, which would have revealed inconsistencies in his account of the alleged abuse.

Officers seemed keen not to upset Beech.

They failed to prioritise the tracing of important witnesses, such as people who worked alongside some of the accused at the relevant time.

Some of them were not initially approached because officers wanted to avoid upsetting Beech, who kept expressing discomfort and demanding updates on progress.

For example, his mother was not contacted for more than six months, even though her son had been living with her throughout the period under investigation.

It took them longer to contact Beech’s ex-wife, Dawn, who would eventually give evidence against him at trial.

Officers also took months to trace all of the boys called Scott from Beech’s secondary school to rule out the possibility that any had been murdered in Kingston. Two detectives were also unnecessarily sent to Australia to speak to one former student in person.

Beech was also helped by Met detectives to get a claim processed that he had previously made to the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority, following the allegations he made to Wiltshire police.

The information contained in this claim was inconsistent with the story that he had told the Met.

Beech eventually received a payout of £22,000, some of which he used to buy an expensive Ford Mustang. Pictures of the car were uploaded to his Facebook page with Beech declaring that it had “always been a dream” to own the convertible.

In terms of the investigation, Beech was keen to keep across details of the case, pestering officers about whether arrests were imminent, and insisting that he wanted the case to go to court.

Who is ‘Fred’?

Police were desperate to speak to a man who Beech claimed was abused alongside him as a child and had witnessed one of the alleged murders.

He claimed he was still in touch with this man, who was given the name “Fred”, and agreed to pass on emails from the police. A psychologist Dr Elly Hanson, then acted as a go-between for the police. She wrote that Operation Midland was “committed to documenting the truth” and would do so “whatever that entails, including exposing prominent people”.

“Fred” appeared reticent to come forward, telling Hanson in an email: “Nick and I went through Hell together but he’s dealt with it a lot better than I ever will.”

“Fred” told police his real name was John, but declined to meet them or elaborate about the allegations, hinting darkly that: “I have received a threat that I take seriously. I have not told Carl about this, but if they can trace me, they can trace him.”

It would transpire later, after detectives from a different force examined the encrypted email account, that the man behind it was Carl Beech himself.

“Fred” was yet another fiction.

Operation Midland started to flounder, but the public turning point came when Harvey Proctor held a furious press conference to denounce both Scotland Yard and Beech’s allegations. He set them out in graphic detail to show the public how implausible they were.

The media, particularly the Daily Mail and the BBC’s Panorama programme, challenged the Met by casting serious doubt on the allegations. Senior officers – including the Commissioner Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe – publicly defended their operation.

Beech himself began withdrawing cooperation and cancelled interviews with police, who now wanted to challenge him on various inconsistencies.

The emails from “Fred” also ceased.

In January 2016, Lord Bramall was told he would face no further action. His wife Avril had died during the inquiry.

The operation ended in March 2016 when Harvey Proctor – the final living suspect – was also told he would face no further investigation.

Both men had been interviewed under caution twice.

Scotland Yard stated that it had investigated the possibility that Martin Allen was one of the alleged murder victims and said they had no reason to believe “Nick” had misled them.

But it was forced to commission a review of the investigation, which was carried out by Sir Richard Henriques.

The retired judge’s report was damning. It listed 43 serious errors and said Operation Midland should have been terminated much earlier. It said the inquiry could have been completed without the accused ever having learnt about it.

The Met apologised and later paid compensation to Lord Bramall and the family of Lord Brittan. Harvey Proctor is currently suing the force, which is resisting his claim in the High Court.

Scotland Yard referred Beech for investigation by the independent Northumbria Police.

Detectives arrived at his Gloucester home on 2 November 2016, and what they found there revealed that Beech was himself a paedophile.

Three of his devices – two laptops and an iPad – contained hundreds of child sexual abuse images, including dozens denoting the gravest abuse imagery.

Some of the images had been hidden behind an app that appeared to be calculator.

It also became clear that Beech was a perverted voyeur – he had installed a recording device in a toilet to secretly film a young boy.

Beech, who had volunteered for the NSPCC, was relieved of his position as a governor at two local schools and suspended from his CQC role.

His role would be terminated the following summer – a time when Beech was charged with six counts relating to the images and one count of voyeurism.

A year later he was charged with 12 counts of perverting the course of justice and one of fraud.

The charges detailed the many ways in which he had lied. He had fabricated the murders, invented the paedophile ring, and lied about the serious injuries.

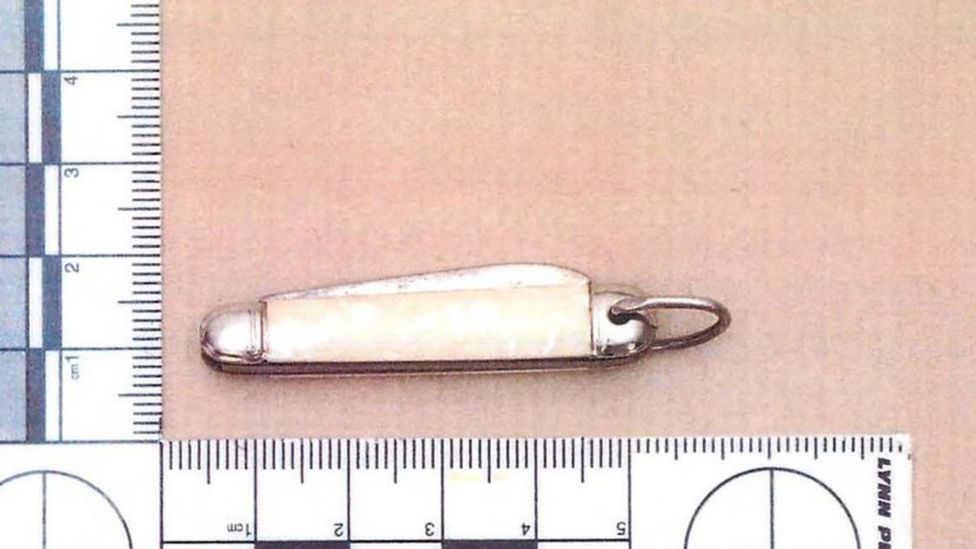

He had given police a small knife – the one he claimed Harvey Proctor had wanted to castrate him with – and two military epaulettes, falsely alleging he had retained them from when he was abused as a child.

The knife had actually been used by his grandmother to cut fruit and had been kept by Beech for years in a “happy memory box”.

Beech, who was on bail, was due to stand trial in Worcester for the sexual offences last summer.

Instead, he went on the run.

When he failed to turn up for his trial at Worcester Crown Court, a warrant was issued for his arrest.

Paedophile fantasies

A manhunt focused on Sweden, where he was known to frequent, and two months later, he was arrested at Gothenburg railway station.

When apprehended, he was in possession of a knife and rope.

Beech had gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid detection. He had bought a remote house in the far north of the country under an assumed name. He moved around using five different aliases, six phones, numerous email addresses and making purchases with untraceable gift cards.

On the first morning of his trial for child sexual offences in January he pleaded guilty to all counts.

But he denied the charges in the larger case, leading to a 12-week trial at Newcastle Crown Court.

The evidence showed he had pieced together his story using the internet to research those he accused.

The sketches he had given to police, suggesting a surprising visual recall of places he was allegedly taken as a child, had been copied from online photographs.

His body lacked scars and injuries and his medical history was free of any such traumas, despite his stories of childhood broken bones, burns, and savage beatings.

School records and former classmates showed he was not absent in the way he alleged.

He based “Fred” – or “John” – on the best man at his wedding, using details about his life to make the pretence more credible.

The best man, who told police he had never been abused by anyone, was not the only former Beech friend falsely dragged into his claims.

His so-called friend Aubrey was based on a childhood acquaintance from Bicester, who was traced and also confirmed that he had not been abused, as alleged.

It also emerged that Beech was a prolific writer of fantasies that had not been published online, some of which were found in his garage or on a memory stick.

The details they contained contradicted his accounts to police, confusing and blending still further the alleged roles of “John”, “Aubrey” and others.

Under cross examination, Beech admitted various parts of the documents, which included his draft memoirs, were fiction.

Beech, who nevertheless insisted most of his claims were true, was totally absorbed in his violent paedophile fantasies, imagining parts for people he knew, then changing their roles and adding in new characters as he went along.

In the witness box, habitually pausing and humming when asked a seemingly unanticipated question about his account, Beech had the look of a man scanning his mind for a lie dressed as a memory.

It seemed natural for him to transpose self-pity into apparent vulnerability and sadness at what he claimed occurred in his childhood.

Prosecutors said his motivations were varied.

Money was one. Beech was in debt and spending beyond his means, including on lavish holidays.

He also enjoyed the attention, with a supportive community of online followers, his media appearances, and access to the police and Parliament all bolstering his sense of self importance.

Beech also seemed to admire – and even to have copied – some of the claims contained in a book by an American alleged abuse victim. His own memoirs and plans to become a speaker at conferences would have provided him with a new income.

In addition, prosecutors regarded his interest in child pornography as central, saying he watched it, possessed it, recorded young boys covertly, and wrote about it over hundreds of pages – all suggesting he also wanted to be a part of it.

Jenny Hopkins, from the Crown Prosecution Service, said Beech was not a fantasist or a victim, but a “manipulative, prolific, deceitful liar” who would have been happy to see innocent men arrested and facing the full force of the law.

Harvey Proctor, who gave evidence at trial, is calling for a fully independent investigation into Operation Midland, which he calls the “worst failing in the history of policing in the last 40 years”.

He said Beech’s “criminality and the Metropolitan Police’s gullibility have threatened the future position of genuine child abuse complainants”.

Lord Bramall, now 95, was not well enough to attend court.

His long-time friend General Sir Hugh Beach gave evidence by video link from his retirement home.

Sir Hugh, 96, was interviewed as a witness – rather than a suspect – by Met detectives.

He says the “mental wear and tear to Lord Bramall must have been enormous in the circumstances”.

He thinks Beech’s crimes are “damaging to the society at large” but “particularly damaging to the people who were the victims of this man’s fabrications.”

Beech is, quite simply, he says, an “evil man”.